《柳叶刀》子刊:饮食与认知功能有何关系?伦敦国王学院的这篇综述说清楚了!

定期阅读学术期刊综述来了解领域最新进展 #生活乐趣# #阅读乐趣# #学术阅读资源#

*仅供医学专业人士阅读参考

2019年,EAT-Lancet委员会在Lancet杂志上发表研究,他们提出了一种可持续的健康参考饮食方案,旨在降低全球非传染性疾病的发生率和死亡率,同时改善粮食系统的可持续性[1]。

饮食方案以植物性成分为主,包括全谷物,水果,蔬菜,坚果,豆类,不饱和食用油,少至中量的海鲜和禽类,无或少量的红肉,加工肉类,添加糖,精制谷物和淀粉类蔬菜。据EAT-Lancet委员会的估计,饮食方案的转变预计每年能减少1080万-1160万的死亡,主要是通过降低饮食相关肥胖和心血管疾病、癌症和糖尿病等非传染性疾病的发生率实现的[1]。

委员会认为,健康饮食不仅应改善身体健康,还应提升精神健康和生活质量,认知功能在这两者中至关重要。作为一种可改变的“环境因素”,饮食与疾病的关系受到了广泛的关注,但研究大多聚焦心脏代谢、癌症和全因死亡。

因此,The Lancet Planetary Health杂志发表了一篇综述文章[2],对不同饮食成分与认知功能间关系的研究证据进行了总结,并据此评估了EAT-Lancet健康参考饮食维持认知功能的能力。

全谷物

全谷物对认知功能的影响在不同的年龄阶段似乎有不同的影响。纵向研究显示,全谷物摄入与儿童10岁时的认知结局无关[3],在不同的认知领域,儿童每天摄入超过46g高纤维谷物,视觉感知和视觉空间推理能力会得到改善[4],而对于青少年来说,9周内,每天摄入360g的混合谷物可以起到保护作用,减少注意力、警觉性和冲动反应诱导的精神疲劳[5]。

全谷物与老年人群认知功能之间的关联较弱,主要包括,黑麦面包可以改善餐后胰岛素反应和葡萄糖耐量这类心脏代谢标志物,并与工作记忆和选择性注意力改善有关[6]。此外,在60岁以上的女性中,全谷物摄入量与简易精神状态检查(MMSE)评估的认知功能改善有关[7]。

对于中青年成年人,目前还没有全谷物摄入与认知功能之间关系的研究。

水果和蔬菜

在蔬菜中,块茎或淀粉类蔬菜是比较特殊的一类,它们对认知功能影响的研究很少,且基本都是很小样本量的研究,通常体现在陈述性记忆的轻微改善。

除此之外的水果和蔬菜是普遍意义上具有有益影响的饮食成分,一项观察性研究的Meta分析显示,增加水果和蔬菜的摄入量与认知障碍风险降低有关[8],但是同样的,在不同年龄段中,研究结果有一些差异。

在儿童和青少年中,健康食品,包括水果和蔬菜在内的摄入量与执行功能呈正相关关系[9]。一项在成年人中进行的前瞻性研究则发现,水果和蔬菜、单独水果,以及富含维生素C的水果和蔬菜摄入量与言语记忆呈正相关关系,但水果和蔬菜、单独蔬菜,以及富含η2-胡萝卜素的水果和蔬菜摄入量与执行功能呈负相关关系[10]。

老年人摄入水果和蔬菜的获益更为明显,高摄入量与认知障碍风险降低26%有关[11],还有研究显示,队列参与者中蔬菜摄入量最低的1/5相比最高的1/5,认知功能相差3.5岁,认知功能下降风险增加100%[12]。

另外,对于老年人来说,蔬菜相比水果可能更加有益。芝加哥健康与老龄化研究[13]显示,6年内,水果和蔬菜的联合摄入量与认知变化之间没有关联,但高蔬菜摄入量与认知功能下降减缓显著相关。每天食用两份及以上蔬菜的人的认知年龄与年轻5岁的人相当[14]。绿叶蔬菜被认为与认知功能具有最强的关联。

乳制品

乳制品对年轻人认知功能影响的研究很少,研究多在老年人中进行,但结果并不一致。一项前瞻性队列研究显示,乳制品的总摄入量与认知功能无关,但牛奶摄入量与言语记忆呈负相关[15]。此外,食用超过每日推荐量乳制品的女性表现出较差的工作记忆[16]。

然而,也有研究表明,乳制品摄入可能对老年人有益。奶酪摄入频率的增加与认知障碍的减轻有关。一项纵向研究表明,与很少摄入乳制品的人相比,乳制品摄入量高的人在整体的认知功能,视觉空间记忆和执行功能方面具有更好的表现[17]。乳制品对认知功能的影响可能受于摄入量,类型和脂肪含量等多种因素的影响,需要进一步进行更详细的研究[18]。

不同来源的蛋白质

日常生活中,蛋白质的来源主要包括肉、鱼、蛋和豆类。

肉类对认知功能的影响似乎并不算坏。一项针对成年人的系统性综述显示,总肉类摄入与认知障碍之间没有关联[19],而Meta分析显示,每周食用一次及以上肉类的人出现认知障碍的风险降低,但增加红肉摄入量与部分认知功能降低有关,例如流体智力和记忆表现[20]。

老年人的证据基础很小,红肉的摄入量通常与认知缺陷有关,但可能在特定认知领域具有较弱的保护作用。

鱼类摄入与认知功能之间的关系很复杂,因为鱼类既含有长链n-3多不饱和脂肪酸,也可能富集了汞和二噁英等有毒物质。因此,鱼类摄入量与认知功能之间的关系通常是非线性的,认知功能提高的水平随着摄入量增加而逐渐下降,当超过推荐摄入量,或是血浆汞浓度超过一定值时,可能会抵消益处,甚至对认知功能有害[21,22]。

鱼类摄入对老年人认知功能的保护作用已经在很多研究中得到证实。日本的队列研究显示,鱼类摄入与痴呆症呈负相关关系,如果摄入量能够达到最高组的水平(>85.7g/天),预计能够在全球范围内,减少5.6%,即260万痴呆症患者[23]。

鸡蛋和豆类摄入与认知功能影响的研究很少,鸡蛋与健康人和长远的认知变化之间没有显著关联,高总豆类和豆制品摄入对女性的认知功能似乎有益处。

坚果

有证据表明,坚果可能会对认知功能产生积极影响。在老年女性中开展的大样本研究显示,对于研究中涉及的所有认知结果,长期高坚果摄入量与它们存在正相关关系,此外,每周至少摄入5份坚果的女性比不摄入的具有更好的整体认知能力[24]。

中国健康与营养调查队列研究也发现,每天摄入超过10g坚果的参与者与不足10g的相比,有更高的整体认知功能评分[25]。

然而,一项随机对照试验的结果[26]与这些发现相矛盾,与没有摄入核桃的对照组相比,添加核桃的干预组在2年中没有显示出认知能力下降的延迟。不过,这项试验在两个不同的地点进行,其中一地的部分干预组参与者表现出整体认知改善,他们相比对照组受教育程度较低,饮食中α-亚麻酸的含量较低,功能性MRI检查显示,他们在工作记忆任务期间的功能性大脑活动显著降低,表明大脑效率有所提高。

总脂肪酸和特定脂肪酸以及脂肪来源

一项研究显示,饱和脂肪摄入量低的儿童,认知灵活性得到改善,而饱和脂肪和胆固醇摄入量高与工作记忆和认知调控受损有关[27],不过类似关联在年轻的成年人中并未观察到。

在中年人中开展的纵向研究表明,基线平均年龄为50岁的中年人,从奶制品中摄入大量饱和脂肪酸与整体认知功能受损有关,此外,饱和脂肪摄入增加与轻度认知障碍(MCI)风险增加有关[28]。

在老年人中,总脂肪摄入量与认知能力下降无关,但高饱和脂肪摄入量与认知障碍风险增加40%有关[29]。

糖和甜味剂

对于儿童和成人来说,糖的摄入对认知功能的影响在不同的研究中结果并不一致,对儿童认知功能影响的结果集中在无影响和有不利影响上[30-32],值得注意的是,发现不利影响的研究[30]中,母亲孕期和儿童的糖摄入量超过了EAT-Lancet健康参考饮食中的建议摄入量,而成人的结果集中在无影响和有有利影响上[32,33],有利影响表现在言语记忆评估中的即时回忆任务方面[33]。

和糖相比,甜味剂的摄入通常被发现不利于认知功能,多项研究表明,阿斯巴甜与较差的认知功能有关[34,35],一项在成人中进行的小型交叉研究还显示,连续8天的高阿斯巴甜饮食会导致更差的空间定位能力[36]。

对于老年人来说,糖和甜味剂在多个研究中均被发现对认知功能有不利影响。一项探索性分析显示,高果糖和葡萄糖摄入量与MCI有关,基于总糖、蔗糖和游离糖摄入量,摄入量高的一组(68.82g/天)相比较低的一组(26.22g/天),认知障碍风险增加2.3-2.6倍[37]。波多黎各的一项研究也有类似的发现,总糖摄入量每增加60g,MMSE评分减少0.4分[38]。

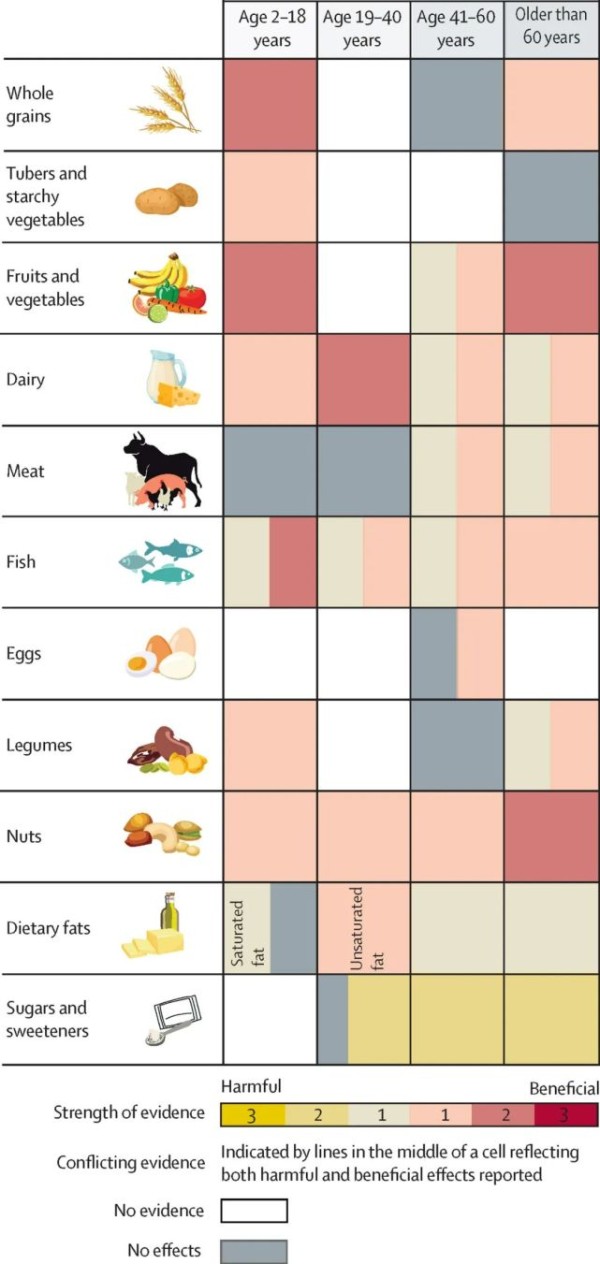

根据综述中的研究证据总结的每类饮食成分在不同生命阶段对认知功能的影响(由黄至红为有害至有益,白色为无证据,灰色为无影响)

由本综述中列举的研究可以看出,大多数研究证据是基于横断面分析,尽管样本量大,并控制了潜在的混杂因素,但并未提供因果结论,且依赖于自我报告,存在一定的偏倚。另外,研究通常没有对年龄和食物进行较细的分组,例如,豆类基本上只包含大豆,海鲜只考虑了鱼类,食物烹调方法也不统一,这对食物中营养成分的含量有显著影响。

总之,未来需要更多的高质量且有力的因果证据研究表明某一类食物在整个生命过程中对认知的影响,我们对饮食的关注也不应局限在降低非传染性疾病发病率和死亡率的角度,而是要扩大对饮食影响的认识,从不同维度来评估饮食质量。

参考文献:

[1] Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems[J]. The Lancet, 2019, 393(10170): 447-492.

[2] Dalile B, Kim C, Challinor A, et al. The EAT–Lancet reference diet and cognitive function across the life course[J]. The Lancet Planetary Health, 2022, 6(9): e749-e759.

[3] Nyaradi A, Li J, Hickling S, et al. Diet in the early years of life influences cognitive outcomes at 10 years: a prospective cohort study[J]. Acta Paediatrica, 2013, 102(12): 1165-1173.

[4] Haapala E A, Eloranta A M, Venäläinen T, et al. Associations of diet quality with cognition in children–the Physical Activity and Nutrition in Children Study[J]. British journal of nutrition, 2015, 114(7): 1080-1087.

[5] Chung Y C, Park C H, Kwon H K, et al. Improved cognitive performance following supplementation with a mixed-grain diet in high school students: a randomized controlled trial[J]. Nutrition, 2012, 28(2): 165-172.

[6] Sandberg J C, Björck I M E, Nilsson A C. Impact of rye-based evening meals on cognitive functions, mood and cardiometabolic risk factors: a randomized controlled study in healthy middle-aged subjects[J]. Nutrition journal, 2018, 17(1): 1-14.

[7] Lee L, Kang S A, Lee H O, et al. Relationships between dietary intake and cognitive function level in Korean elderly people[J]. Public health, 2001, 115(2): 133-138.

[8] Mottaghi T, Amirabdollahian F, Haghighatdoost F. Fruit and vegetable intake and cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. European journal of clinical nutrition, 2018, 72(10): 1336-1344.

[9] Cohen J F W, Gorski M T, Gruber S A, et al. The effect of healthy dietary consumption on executive cognitive functioning in children and adolescents: a systematic review[J]. British Journal of Nutrition, 2016, 116(6): 989-1000.

[10] Péneau S, Galan P, Jeandel C, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and cognitive function in the SU. VI. MAX 2 prospective study[J]. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 2011, 94(5): 1295-1303.

[11] Wu L, Sun D, Tan Y. Intake of fruit and vegetables and the incident risk of cognitive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies[J]. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 2017, 21(10): 1284-1290.

[12] Nooyens A C J, Bueno-de-Mesquita H B, van Boxtel M P J, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and cognitive decline in middle-aged men and women: the Doetinchem Cohort Study[J]. British journal of nutrition, 2011, 106(5): 752-761.

[13] Bienias J L, Beckett L A, Bennett D A, et al. Design of the Chicago health and aging project (CHAP)[J]. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 2003, 5(5): 349-355.

[14] Morris M C, Evans D A, Tangney C C, et al. Associations of vegetable and fruit consumption with age-related cognitive change[J]. Neurology, 2006, 67(8): 1370-1376.

[15] Hercberg S, Preziosi P, Briançon S, et al. A primary prevention trial using nutritional doses of antioxidant vitamins and minerals in cardiovascular diseases and cancers in a general population: the SU. VI. MAX study—design, methods, and participant characteristics[J]. Controlled clinical trials, 1998, 19(4): 336-351.

[16] Kesse-Guyot E, Assmann K E, Andreeva V A, et al. Consumption of dairy products and cognitive functioning: findings from the SU. VI. MAX 2 study[J]. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 2016, 20(2): 128-137.

[17] Rahman A, Baker P S, Allman R M, et al. Dietary factors and cognitive impairment in community-dwelling elderly[J]. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 2007, 11(1): 49.

[18] Crichton G E, Elias M F, Dore G A, et al. Relation between dairy food intake and cognitive function: The Maine-Syracuse Longitudinal Study[J]. International dairy journal, 2012, 22(1): 15-23.

[19] Zhang H, Hardie L, Bawajeeh A O, et al. Meat consumption, cognitive function and disorders: a systematic review with narrative synthesis and meta-analysis[J]. Nutrients, 2020, 12(5): 1528.

[20] Zhang H, Cade J, Hadie L. Consumption of red meat is negatively associated with cognitive function: A cross-sectional analysis of UK Biobank[J]. Current Developments in Nutrition, 2020, 4(Supplement_2): 1510-1510.

[21] De Groot R H M, Ouwehand C, Jolles J. Eating the right amount of fish: inverted U-shape association between fish consumption and cognitive performance and academic achievement in Dutch adolescents[J]. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 2012, 86(3): 113-117.

[22] Masley S C, Masley L V, Gualtieri C T. Effect of mercury levels and seafood intake on cognitive function in middle-aged adults[J]. Integr Med, 2012, 11(3): 32-39.

[23] Tsurumaki N, Zhang S, Tomata Y, et al. Fish consumption and risk of incident dementia in elderly Japanese: the Ohsaki cohort 2006 study[J]. British Journal of Nutrition, 2019, 122(10): 1182-1191.

[24] O’Brien J, Okereke O, Devore E, et al. Long-term intake of nuts in relation to cognitive function in older women[J]. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 2014, 18(5): 496-502.

[25] Zhang B, Zhai F Y, Du S F, et al. The C hina H ealth and N utrition S urvey, 1989–2011[J]. Obesity reviews, 2014, 15: 2-7.

[26] Sala-Vila A, Valls-Pedret C, Rajaram S, et al. Effect of a 2-year diet intervention with walnuts on cognitive decline. The Walnuts And Healthy Aging (WAHA) study: a randomized controlled trial[J]. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 2020, 111(3): 590-600.

[27] Khan N A, Raine L B, Drollette E S, et al. The relation of saturated fats and dietary cholesterol to childhood cognitive flexibility[J]. Appetite, 2015, 93: 51-56.

[28] Eskelinen M H, Ngandu T, Helkala E L, et al. Fat intake at midlife and cognitive impairment later in life: a population‐based CAIDE study[J]. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: A journal of the psychiatry of late life and allied sciences, 2008, 23(7): 741-747.

[29] Cao G Y, Li M, Han L, et al. Dietary fat intake and cognitive function among older populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer's Disease, 2019, 6(3): 204-211.

[30] Wei M, Brandhorst S, Shelehchi M, et al. Fasting-mimicking diet and markers/risk factors for aging, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease[J]. Science translational medicine, 2017, 9(377): eaai8700.

[31] Wolraich M L, Wilson D B, White J W. The effect of sugar on behavior or cognition in children: a meta-analysis[J]. Jama, 1995, 274(20): 1617-1621.

[32] Toews I, Lohner S, de Gaudry D K, et al. Association between intake of non-sugar sweeteners and health outcomes: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials and observational studies[J]. bmj, 2019, 364.

[33] García C R, Piernas C, Martínez-Rodríguez A, et al. Effect of glucose and sucrose on cognition in healthy humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies[J]. Nutrition Reviews, 2021, 79(2): 171-187.

[34] Sünram-Lea S I, Foster J K, Durlach P, et al. Investigation into the significance of task difficulty and divided allocation of resources on the glucose memory facilitation effect[J]. Psychopharmacology, 2002, 160(4): 387-397.

[35] Harte C B, Kanarek R B. The effects of nicotine and sucrose on spatial memory and attention[J]. Nutritional Neuroscience, 2004, 7: 121-125.

[36] Lindseth G N, Coolahan S E, Petros T V, et al. Neurobehavioral effects of aspartame consumption[J]. Research in nursing & health, 2014, 37(3): 185-193.

[37] Chong C P, Shahar S, Haron H, et al. Habitual sugar intake and cognitive impairment among multi-ethnic Malaysian older adults[J]. Clinical interventions in aging, 2019, 14: 1331.

[38] Ye X, Gao X, Scott T, et al. Habitual sugar intake and cognitive function among middle-aged and older Puerto Ricans without diabetes[J]. British journal of nutrition, 2011, 106(9): 1423-1432.

本文作者丨应雨妍

网址:《柳叶刀》子刊:饮食与认知功能有何关系?伦敦国王学院的这篇综述说清楚了! https://www.yuejiaxmz.com/news/view/1273596

相关内容

逆转糖尿病!柳叶刀子刊:真实世界研究,限制热量,超3成糖尿病缓解柳叶刀:地球人 请换成这种全新的饮食模式

柳叶刀:中国癌症与饮食息息相关

减肥就能缓解糖尿病?柳叶刀子刊:减到这个数,近50%患者完全缓解

【科普营养】柳叶刀:地球人,请换成这种全新的饮食模式

柳叶刀子刊:保护肠道健康,日常生活做好这5点

《柳叶刀》子刊:5个行为,可延寿8

柳叶刀重磅综述:成人肥胖症的现代医学疗法

《柳叶刀》研究揭示全球及中国饮食结构与死亡、疾病负担的紧密联系

Lancet Public Health:柳叶刀子刊:25年超过43万人研究:低碳水化合物饮食缩短寿命!